Evi & Walter: A love story in any key

DAY ONE & TWO

By Stefano Esposito

Photos and Video by Ashlee Rezin

On the second coldest day of the year, in a February more frigid than any since the late 1880s, Walter and Evi Levin slowly head out from their Hyde Park retirement apartment for the van ride downtown to Symphony Center.

The Levins, who are in their 90s, are dressed nearly identically, in matching parkas, thick sweaters, gray pants, scarves and fuzzy mittens.

Watch Evi & Walter: Day One. Watch the full video here.

But in almost every other way, they couldn’t appear more different.

Walter towers above tiny Evi, who has an elfin face and the slightly mussed hair of a woman with better things to do than spend an hour looking in a mirror.

Taking a seat in the van, she smiles to find herself with other people. It’s hard to be alone with Walter all the time.

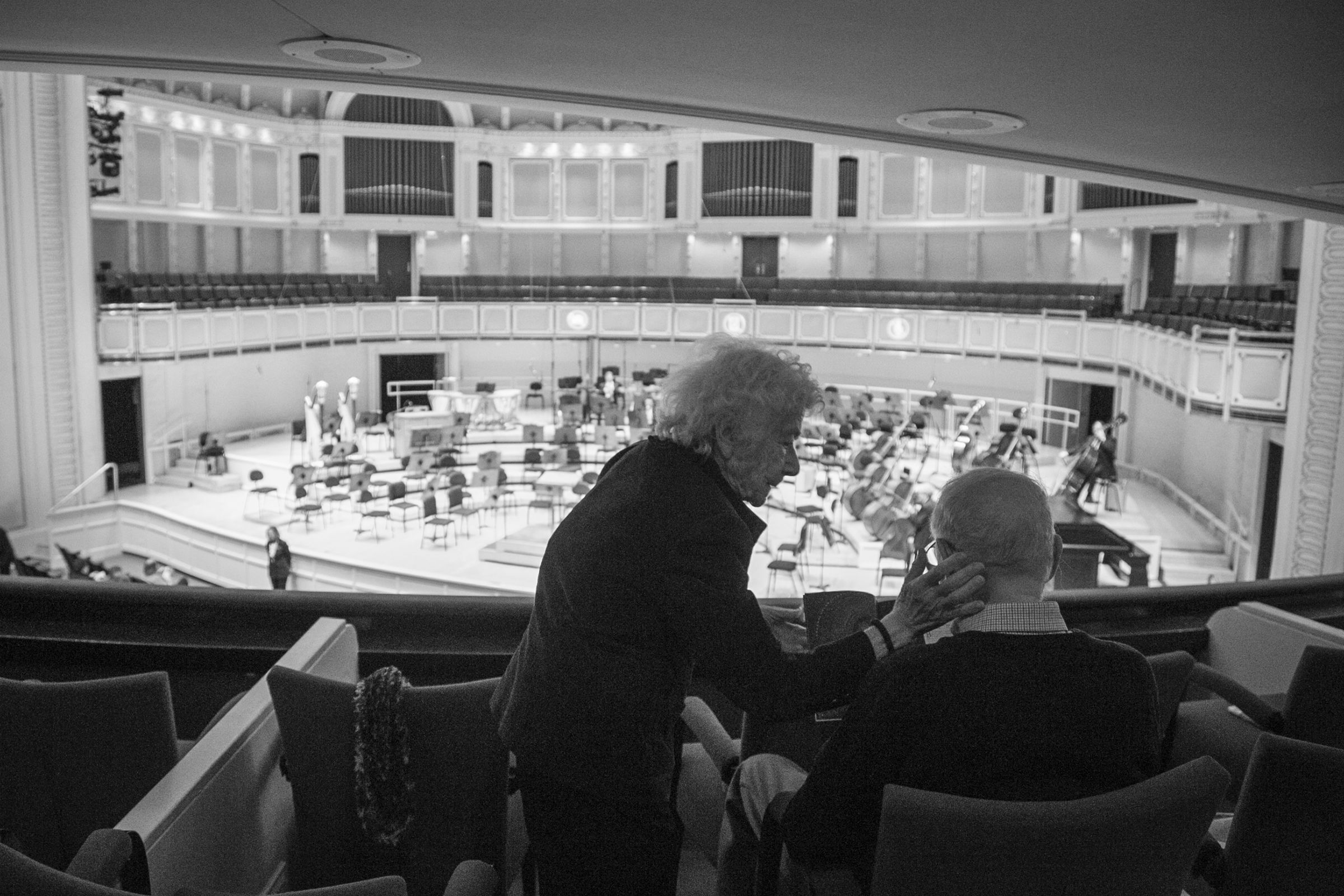

Evi Levin checks on her husband of 66 years, Walter Levin, before a performance at Symphony Center.

During the ride downtown, she is animated. She talks about the flight to freedom from the Nazis that her family once made. And she tells the story of how her belief in romantic love withered 70 years ago, when her first husband went back to Bulgaria, abandoning her.

“I didn’t want to see any man,” Evi says. “It was such a horrible experience. I’ve never recovered from that.”

Walter and Evi hold hands at Montgomery Place in Hyde Park, where the couple live. Evi, 92, says Walter is the center of her world, but it’s a very different life from the one they formerly shared — one filled with conversations about art, music and philosophy.

Walter is her second husband. They’ve been married for 66 years. He sits beside her in the seat by the window, serene. He doesn’t look out the window, just stares at the back of the seat in front of him.

He doesn’t join in the conversation. It’s not even clear he’s aware Evi is speaking.

She reaches over, rubs his hand and, in his native German, asks: “Are you OK, Walter?”

He nods. Nothing more.

It has been like this for most of the past four years. That’s when Walter — once a renowned musician and teacher, with the great American conductor James Levine at one time among his students — was given the diagnosis: dementia.

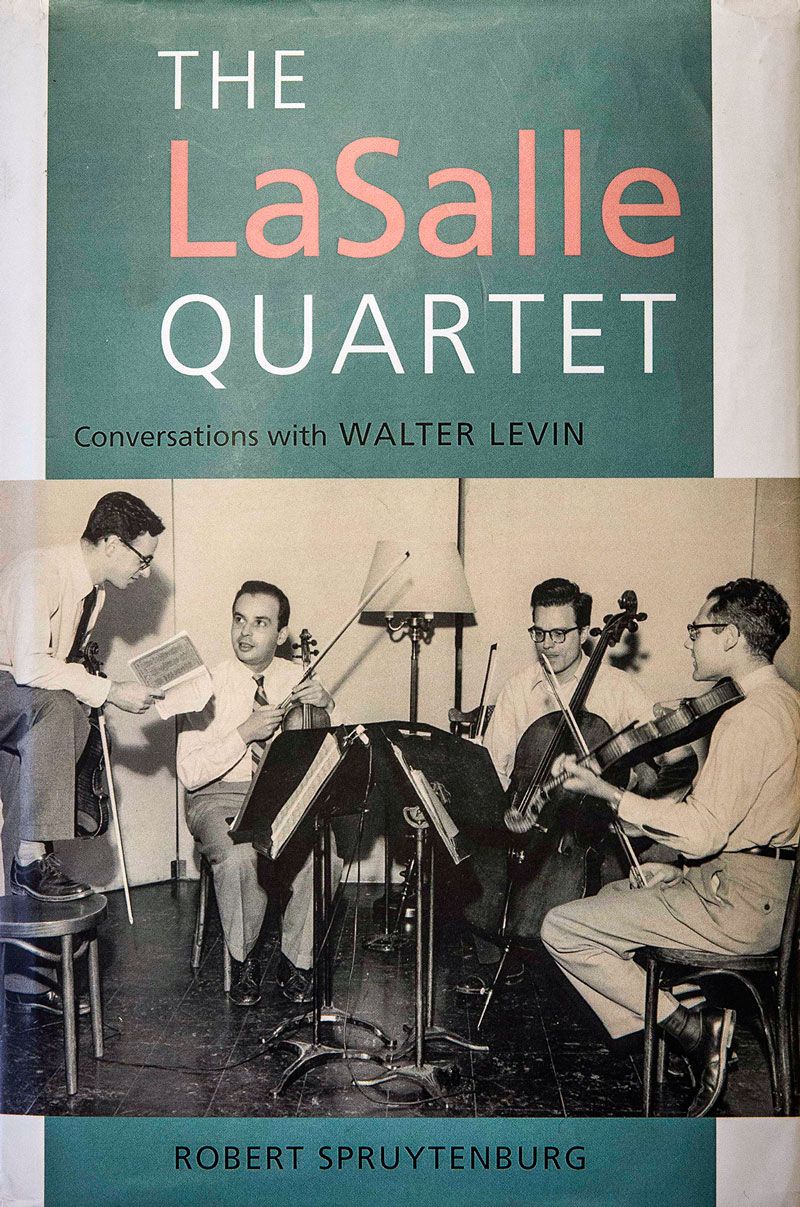

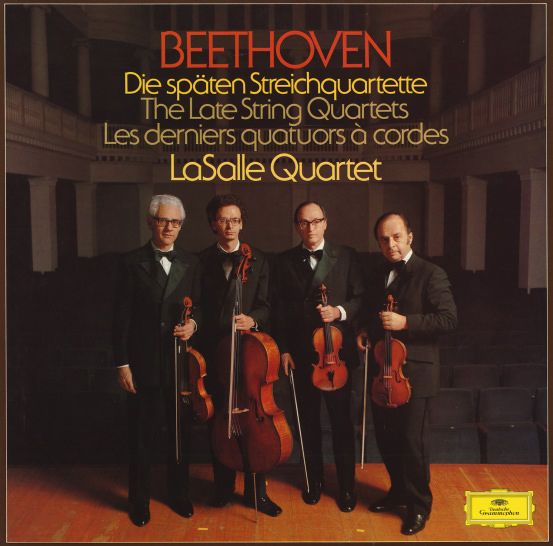

He’d spent 40 years traveling the world, playing chamber music’s most demanding pieces as the founder of and first violin for the celebrated LaSalle Quartet.

Beyond playing, there was his teaching. When you aspired to play the violin professionally, you wanted to study with Walter Levin, despite his famously volcanic temper.

Walter led. Others followed.

Now, it’s Evi who leads. She orchestrates every aspect of Walter’s life, from putting his All-Bran cereal before him each morning to picking the mittens he’ll wear.

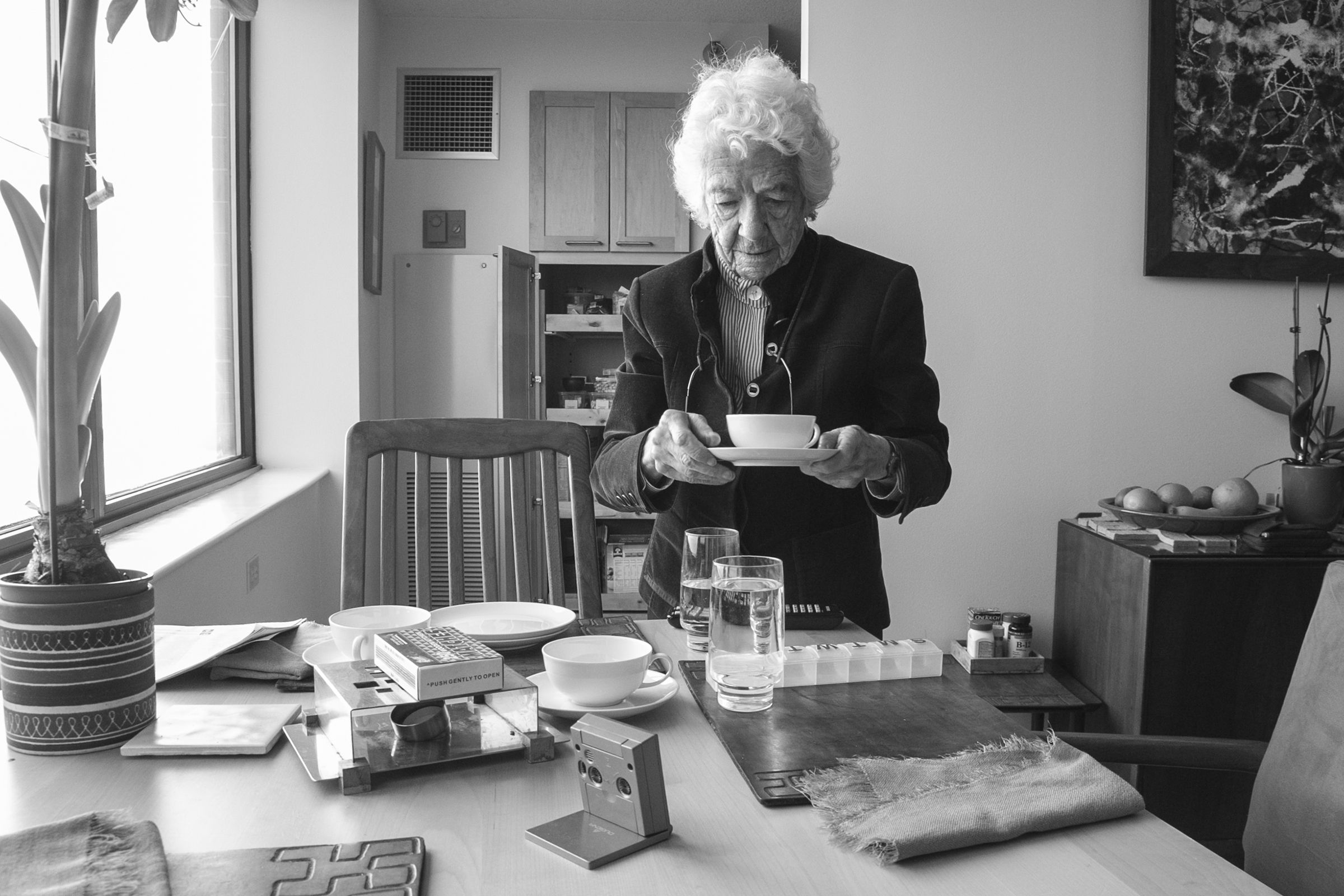

Evi prepares Walter’s tea in the couple’s apartment overlooking Lake Michigan. Walter now depends on Evi for almost everything.

The music — his life and love for so long — still lives, if only in fragments somewhere deep in Walter’s mind. For now, at least.

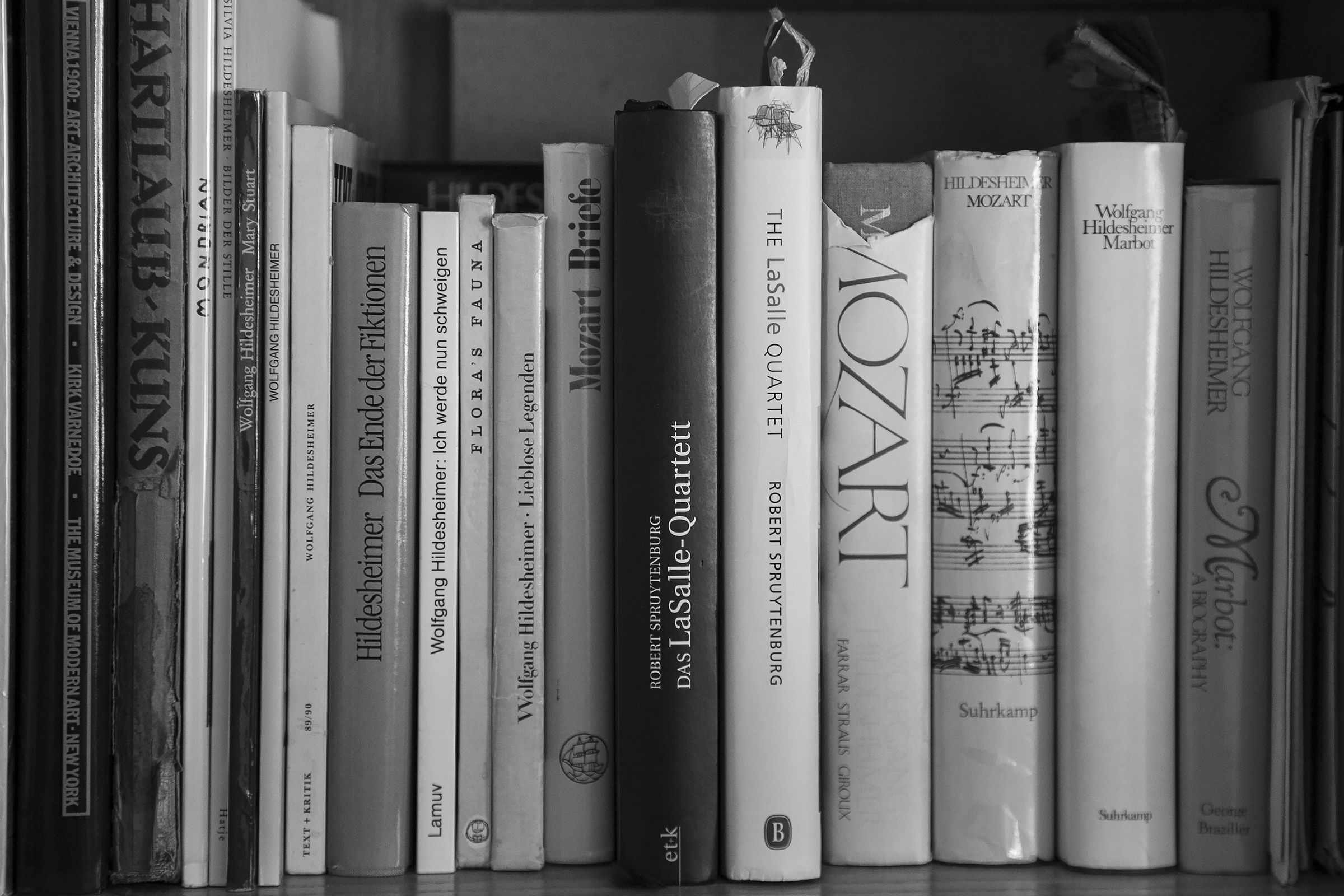

At home, it surrounds the couple — musical scores, the paper brittle with age, and countless CDs filling shelves floor to ceiling in their bedroom.

For whatever time together they have left, Evi has made it her mission to help draw the music to the surface whenever and however she can.

At Orchestra Hall, Evi removes Walter’s mittens. She pulls back the hood of his parka. Along with other elderly music lovers from Montgomery Place, where they live, the Levins inch their way inside to hear maestro Riccardo Muti conduct a rehearsal of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Walter and Evi find seats. She rubs his knee. He opens his program. The all-Mozart concert includes the composer’s great unfinished work — the Requiem in D Minor.

Muti steps to the podium, and Walter’s gaze shifts from program to stage. The house lights dim.

The Requiem is mournful, majestic — a mass in which a choir of 100 voices asks God to deliver his faithful souls “from the pit of destruction ... that the grave devour them not, that they go not down to the realms of darkness.”

As stirring as the music is the story behind it. A mysterious messenger clad in gray requested the piece in 1791 for his anonymous master. While composing the piece, Mozart fell ill. His mind in turmoil, some say he came to fear he was being poisoned — and believed he was composing the requiem for his own funeral.

He died on Dec. 5, 1791, just 35 years old, leaving this final work for others to complete. No one knows what killed him.

During the rehearsal, the pianist stops midway through another piece, Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24, and walks over to Muti. They share a moment of whispered conversation, then the maestro turns to address someone in the audience who’s holding up a cell phone.

“You can film, but then you have to pay a lot of money,” Muti says, shaming the visitor into putting away the phone.

Walter and Evi at Symphony Center. Walter rarely speaks these days unless asked a question.

Throughout it all, Walter stares straight ahead, his eyes blinking with the slow, steady beat of a leaky faucet.

Nearly two hours into the rehearsal, Evi whispers, “I think I have to take Walter to the men’s room.”

Later, in the lobby, Evi wraps Walter against the cold, and a question is put to him: What did he think of the performance?

“It’s such a fabulous piece,” he says.

It’s all he says.

A decade or so earlier, writer Robert Spruytenburg interviewed him for the biography “The LaSalle Quartet, Conversations with Walter Levin.” Back then, the retired violinist had this to say about the same piece:

“The key of D minor had a very special meaning for Mozart. For him, it was virtually a key of mourning, of funereal grief, which you can also hear in the D minor piano concerto, … and the last of his works, the Requiem.”

For a young Walter, music was like the hum of a refrigerator or the tick-tock of a clock — a constant presence at his parents’ home in Berlin.

As a university student, his mother studied piano. She practiced for hours each day while Walter sat on a stool at her feet. Friends sometimes joined Erna Levin, playing the chamber music to which Walter would later devote his life.

Walter learned to play by ear. When family friends realized he had ability, they brought him instruments — an accordion, a harmonica, a drum, a trumpet, a violin. He taught himself to play all of them. At an age when most kids had little on their minds besides the start of first grade, Walter already knew he wanted to spend his life playing the violin.

A young Walter playing the violin.

The Nazis came to power when Walter was just 9. In the eyes of classmates who’d been his friends, he now saw hate. One called him a “dirty rotten Jew.”

“I punched the boy in the mouth and knocked one of his teeth out,” Walter recalled in his biography.

Like many German Jews, the Levin family fled to Palestine, where Walter devoted himself to the violin.

But he always wanted to study in America — in New York, “the mecca of music,” he called it. At 21, he left his family behind in Palestine, and, after a two-month journey on a steam freighter, Walter arrived in the United States in February 1946.

Evi’s childhood in Bulgaria also was filled with music. Her parents brought singers and conductors to their home, a place so grand it had a separate apartment for guests with its own servants and chauffeur. Evi was a piano prodigy.

“But I never wanted to be a pianist,” she says, “because it’s such a lonely profession.”

On morning horseback rides, Evi’s parents often bumped into the country’s king, Boris.

But come 1939, money and social standing mattered little if, like Evi’s family, a big, red “J,” for Jew, was stamped in your passport. Her father, an exporter, was banished from Bulgaria. The family fled first to Italy before making the short crossing by boat to Barcelona.

All the passengers were allowed to disembark there — except Evi’s family. They sat on the deck with their luggage, anxious. The crew prepared to return to Italy. A man in a military officer’s uniform, shrieking fascist slogans, boarded the boat.

“He goes over to my father, whispers in his ear, ‘I’m a Hungarian Jew. Come with me,’” Evi remembers.

The uniform had been stolen from a corpse. The man led the family ashore, where friends of Evi’s father awaited them.

For the next six months, the family lived in Spain on phony visas. They went from one foreign consulate to another in search of legitimate papers to deliver them from Nazi Europe.

It would be more than a year after leaving Bulgaria that the family, traveling on U.S. visas, finally arrived in New York.

For her parents, the journey from Bulgaria to America was a time of crisis. For a young Evi, though, it helped her learn that life is filled with jarring turns, and you need to adapt.

Evi did not marry Walter for love.

“I’ve never heard her say that,” Tom Levin, one of the Levins’ two children, says when asked.

Yet it’s hard to look at Walter and Evi today and see anything but love.

“If that isn't love, I don't know what is.”

—Tom Levin, one of the Levins’ two children

Except for when he is with his caregiver, she is with him everywhere he goes.

“If that isn’t love, I don’t know what is,” says the son, a Princeton University professor who teaches media and cultural theory in the German department.

In 1948, Evi, then 25, already was divorced. She’d married a man in New York — like her, a native Bulgarian. At the end of World War II, he told her he was going home to see his family. He never returned. Desperate, Evi reached out to everyone she knew in Bulgaria. She thought perhaps Soviet agents had seized her husband.

“Finally, I get a letter, saying, ‘I wish you would get off my back,’ ” Evi says. “ ‘I have to take care of my parents. I’m busy here. Our marriage didn’t work out anyway. So I’m asking for a divorce.’

“I fell from way up here down to hell.”

So Evi had a jaded view of love when she met Walter in 1948. A mutual friend brought Walter to meet her at Evi’s mother’s house in Forest Hills, New York. Walter was fuming that he’d just lost the second violinist for his new quartet.

“Oh, I loved that intensity!” Evi says.

In Walter — slender, with glasses, a prominent forehead and long, narrow nose — she saw a chance not for love but to live a grand life filled with music.

“Because of the first marriage, which killed my illusions that you get married for love … I loved the fact that I would have music all the time, without having to perform it myself,” Evi says.

They married in 1949 in Colorado, where Walter’s quartet was in residence at Colorado College. Evi was registering for classes there. She was told they would be free if she were married to Walter.

“I said, ‘Come on, Walter, we have to go to city hall to get married,’ ” Evi says. “We called the second violinist as a witness.”

There were no guests, no white dress, not even a wedding ring. Evi still won’t wear a ring. She considers it a hollow symbol of love.

Walter and Evi in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 1965. Evi spent much of her childhood in the Bulgarian capital, forced to flee by the Nazis’ rise to power.

The LaSalle Quartet’s tours — 67 of them in 40 years — took the couple across the globe. Beyond North America, there were concerts in Europe, Australia, India, Thailand, the Fiji Islands.

There were best-selling recordings, too, on the Deutsche Grammophon label, and an appearance in 1965 on the “Today” show, with Barbara Walters.

Behind the scenes, there was always Evi. She was Walter’s agent as well as the quartet’s unofficial record-keeper and historian. She collected concert programs, photographs, letters — all still preserved in 15 scrapbooks.

As a musician, Walter was demanding, exasperating at times. It was, after all, his quartet. And things would be done his way.

He’d insist that to understand a piece — to truly grasp what Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart were trying to express — you had to learn all of the parts, what each instrument would play, not just your own.

He likened playing music to rehearsing Shakespeare.

“Imagine coming to the first rehearsal and saying, ‘I’m supposed to play a guy called Othello,’” Walter explained in his biography. “‘And you? Who are you? Desdemona! Who’s that? I don’t know the piece. I’ve just learned my own part.’”

Were there musicians who couldn’t handle Walter’s exacting standards?

“That’s an understatement,” says Tom Levin.

The Levins divided their home life between Cincinnati, where the quartet was in residence at the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music beginning in 1953, and Switzerland, where the musicians spent summers rehearsing.

Both of the couple’s children — Tom and David — remember their father as brilliant and uncompromising, someone who saw life as far too short to squander watching TV or just getting by in school.

“All of my friends, their parents would be delighted if they got a B-plus,” says David Levin, a University of Chicago professor who teaches, among other subjects, opera studies. “My parents were like, ‘What the hell is going on?’”

Tom Levin speaks of his youth with ambivalence. He remembers seeing his father on stage, on record covers, but rarely at home.

“All my childhood, we were basically getting to a point where we could have a meal with my father because [that] would mean you had something to say and something to talk about because he was not somebody who could talk about kid stuff,” he says.

Evi puts it this way: “He was absent. He was not a dad. He didn’t like children.”

For fun, the family might put on a classical music radio station.

“Naming the piece took about three or four seconds. … In the house that I grew up in, the real game that my parents played was not ‘name that piece,’ but ‘who is playing?’” Tom Levin says.

The sons agree, though, that their father’s high standards — for himself and for them — helped them to find a focus in life. They also agree on the role of their mother.

“If we didn’t have a mother who was such an extraordinary, generous, deeply warm human being, neither my brother nor I would be the happy, healthy, well-tempered creatures that we are,” Tom Levin says.

Classical music instructors aren’t like other teachers. Violist Jan Gruning, who plays with Cincinnati’s Ariel Quartet, tells the story of a cellist friend who studied many years ago with the Hungarian composer Gyorgy Kurtag.

After hearing the student play one of his pieces, Kurtag snarled: “Very, very not good!”

The student devoted himself to the piece, finally earning what he considered a compliment: “Quite bad.”

Walter started teaching full-time in the early 1990s, after his quartet disbanded in 1989, when he was 64.

“Look, they wanted to give up while the quartet was on top and not for people to say, ‘Oh, my God, why don’t they give up?’” Evi says.

Walter developed a reputation in Europe and America as a guru — a feared one.

In 2008, Gruning and the rest of the young Ariel Quartet had been warned about him when they took a master class with him at a school for professional musicians in France. Walter was known to shred egos and eject unprepared students from class. The staff at the school kept Evi close by in case Walter erupted.

“If one time Walter would say, ‘This is good’ … it’s more gratifying than winning the lottery.”

— Ariel Quartet violinist Alexandra Kazovsky

Amit Even-Tov, who plays cello with the quartet, remembers Walter’s reaction the first time they played a Mozart piece.

“‘After you played the introduction, I thought you were stupid, but then you started the allegro, and it was OK,’” Even-Tov recalls him saying.

It was never personal. Teaching for Walter was always about the music.

“What is extremely rewarding is after all this work — all this blood, sweat and tears — if one time Walter would say, ‘This is good,’” says Ariel Quartet violinist Alexandra Kazovsky. “It’s more gratifying than winning the lottery.”

In 2009, dozens of professional musicians Walter had taught over the years gathered in Berlin for a three-day celebration to mark his 85th birthday. The highlight: a concert, broadcast live on German radio, at the Berlin Philharmonie’s Chamber Music Hall.

The hall was packed, including many of Walter and Evi’s friends. Tom and David came from America. Several of the string quartets Walter once taught now played for him.

Then, they called Walter to the stage. Five quartets clustered around and played him “Happy Birthday.”

“It was incredibly moving, and he was delighted,” Tom says.

Backstage, Tom and David brought over a chair should Walter need to rest.

Walter was his witty, charming, slightly sarcastic self. If there were signs then of what was about to come, no one saw them.

Certainly, no one could have foreseen the two terrible accidents that almost killed Walter about a year after that celebration.

DAY TWO

Keeping the music alive