Life on a ledge

By Frank Main | Sept. 25, 2016

The woman was perched on a concrete ledge four stories above Madison Street.

She was a strange sight there in red-and-black pajama bottoms, a black sweatshirt and pink flip-flops. She hung her legs over the side of the building like a kid gathering the courage to jump into chilly water.

Below, construction workers and morning commuters gawked. They feared the worst but couldn’t turn away. A few recognized her, though none knew her well.

At 7:36 a.m., a 911 dispatcher radioed officers: “You got a female sitting on the roof with legs dangling over. Fire is rolling.”

The first cop arrived at the West Loop apartment building — the Luxe, at 1222 W. Madison St. — at 7:43 a.m. He radioed in, confirming what the dispatcher already knew: “There’s somebody on the roof, dangling. There’s a lot of fire equipment out here already.”

Thirty seconds later, he asked to get someone out from the department’s Crisis Intervention Team — somebody trained to deal with mental illness. Already on the way, the dispatcher said, “but you’re going to have to give him a few minutes.”

Firefighters began to inflate the enormous yellow air mattress they carry to break the fall of jumpers. But there was a tree in the way.

So they were preparing instead for a rooftop rescue. That’s when, suddenly, the woman scooted forward and, without a word, launched herself into the air.

At 7:46 a.m., a police officer radioed in: “She jumped!”

“Oh, God!” the dispatcher said. “Was that pillow already inflated?”

“That’s negative,” the officer said.

Listen to police radio traffic.

A paramedic rushed to check for a pulse. He shook his head: “No.” A firefighter covered the body.

There were gasps and screams and sobs. Some people stared in disbelief at the cellphone videos they’d just taken of the woman jumping.

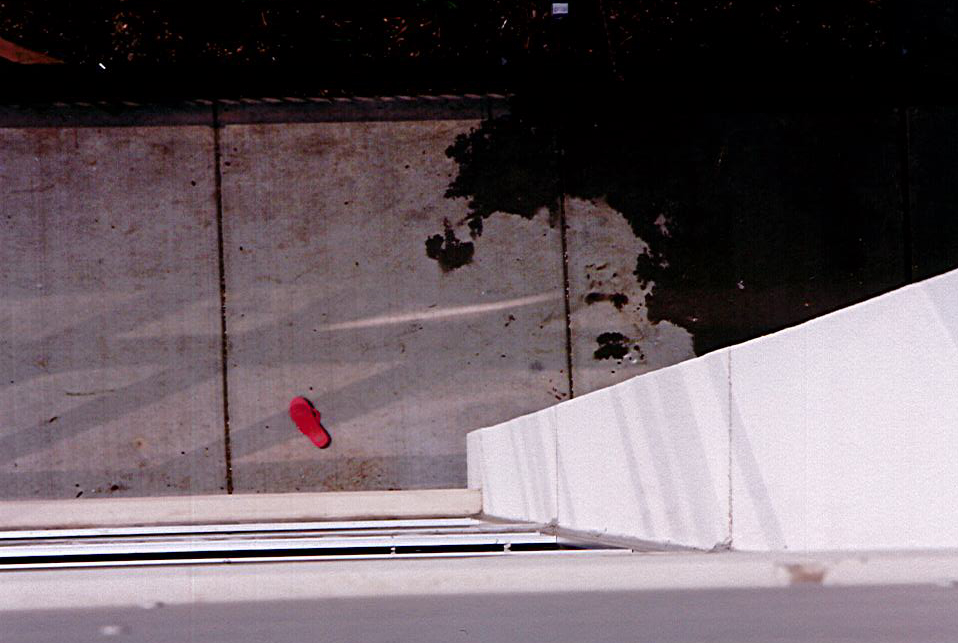

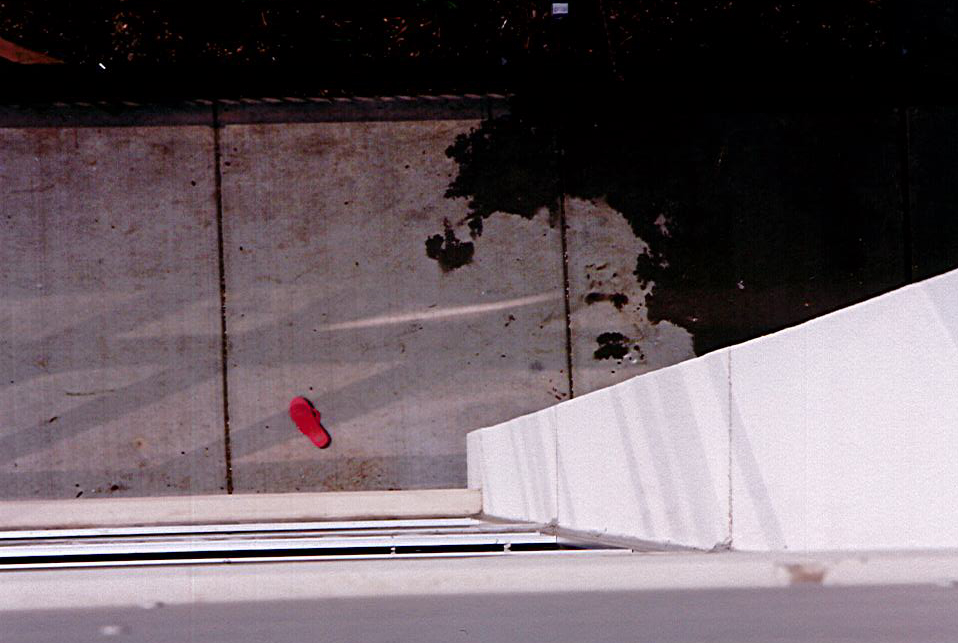

It wasn’t long, though, until the eastbound lanes of Madison Street were opened again, and rush-hour traffic resumed. A CTA No. 20 bus rolled past. A detective got to work. And on the sidewalk one pink flip-flop remained as testament to what happened.

Kendra Smith’s pink flip-flop, seen from the roof. | Chicago Police Department evidence photo

Editor's Note

Rarely do our news reporters refer to themselves by the pronoun “I” in the stories they cover for the Chicago Sun-Times. Personal reflection is normally reserved for columnists.

And rarely does this newspaper publish stories about individual suicides.

The news media, including this newspaper, generally don’t report on suicides unless they have a larger impact on the public. Some exceptions are murder-suicides and stories about public officials who have taken their own lives.

In this case, Sun-Times reporter Frank Main witnessed a woman kill herself in a very public manner. Her suicide, on a busy Chicago street, deeply affected those who saw it — including him. It also took an emotional toll on those who knew the woman.

In this case, Sun-Times reporter Frank Main witnessed a woman kill herself in a very public manner. Her suicide, on a busy Chicago street, deeply affected those who saw it — including him. It also took an emotional toll on those who knew the woman.

Because Main was a witness, he’s using his own voice in this story, documenting the ripple effects of a public suicide — through his own eyes and those of others including the first-responders, other residents of the block, the people who work in his neighborhood and the woman’s family and friends.

I was there. I saw her jump.

I was making coffee, getting ready for work, trying to rouse my 21-year-old son. A neighbor called — an ex-cop.

“Hey, look out your balcony,” he said. “There’s a jumper on the roof on the other side of the street.”

I could see the woman on the ledge.

My son wouldn’t look. “I don’t want that in my brain,” he said.

But I kept checking. The last time I looked, she jumped.

“S---!” I shouted to my son. “She did it.”

It was a sickening sight, a human being plunging to the concrete and death.

My mind raced: Who was she? Why did she do this? And why so publicly?

Newspapers rarely write about suicides. The Chicago Sun-Times didn’t cover this suicide. No one did.

But in talking with my neighbors, the police, the firefighters and eventually her best friends, her boyfriend and her mom, I decided that writing about this would put a face on a person whose suicide sent ripples she probably couldn’t have imagined through the people she touched — with her life and her death.

And, to be honest, I couldn’t get this out of my head.

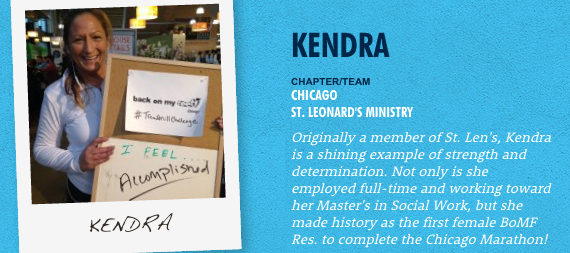

Kendra Smith. | Provided photo

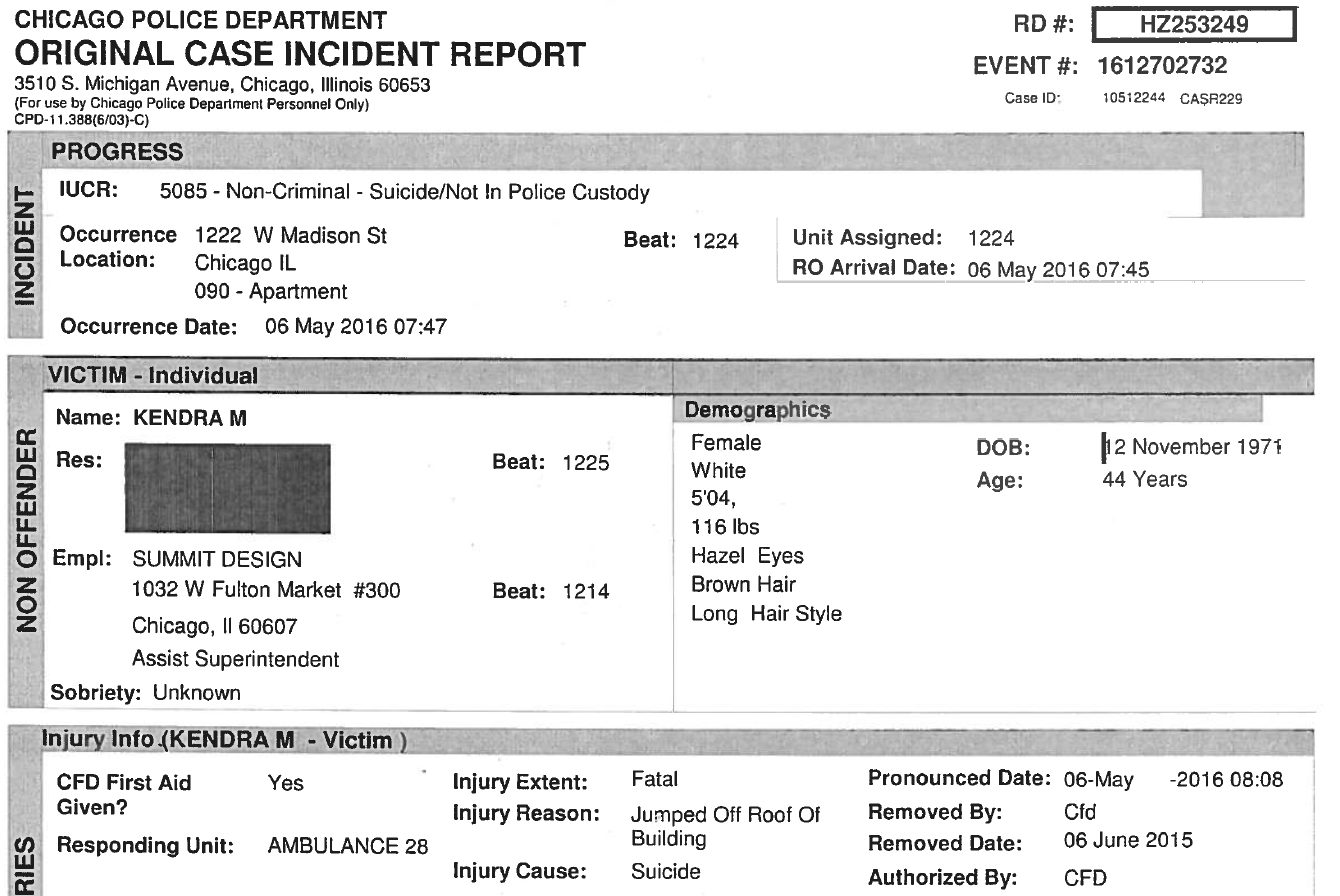

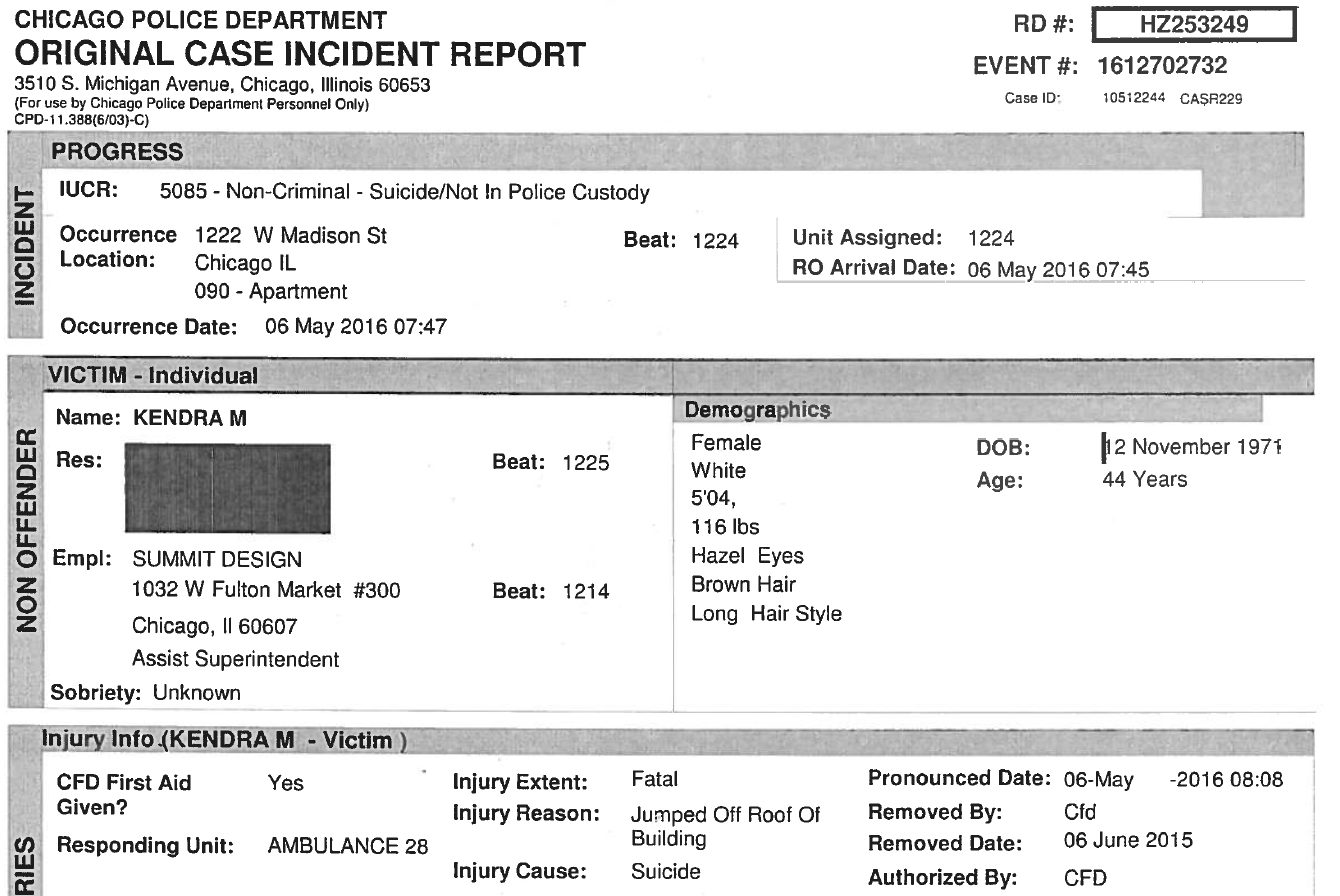

I started with the police report.

Her name was Kendra Smith. Kendra. She was 44, five-feet-four, 116 pounds, with long, brown hair and hazel eyes.

She worked for Summit Design & Build in the West Loop, supervising construction of the rooftop deck at the Luxe. An “exceptional worker,” her boss told the detective investigating her death. No, he had no hint she was having problems.

At 5:18 a.m., Kendra had entered the building by a side door and climbed the stairs to the roof, the police report said.

She stood beside a table for a few minutes and placed her wallet, keys, business cards and iPhone on the roof. Then, she walked to the edge and sat. A security camera captured it all.

It was 5:33 a.m. She stayed on that ledge for more than two hours till she jumped.

In the “Notes” application on her phone, she left a message, asking emergency responders to call and let her mother know.

The detective found text messages, too.

One was sent at 4:28 that morning to a roommate who lived with her and her boyfriend: “Well I’m sure you [two] have conjured everything in the book about my mission my suicide mission. Please take care of each other I paid Comed and peoples gas there will be more information forth with.”

Another, sent a minute later to her 35-year-old boyfriend: “I love you more than life itself but [you’re] too young to deal with this and I’m tired [please] only remember the good times your girl K I truly love you.”

In a nearby parking lot, a police officer found her red, 2013 Toyota Corolla with a bottle of thyroid medicine inside.

The detective spoke with Kendra’s boyfriend, who told him they’d met two years before through a running club, started dating and moved in together. Kendra was suffering from kidney failure and possibly cancer, the boyfriend said. She was stressed over work and about their relationship, he told the detective.

The police report on Kendra Smith’s death ran nine pages. Still, it left more questions than answers.

The answers, it turned out, were complicated.

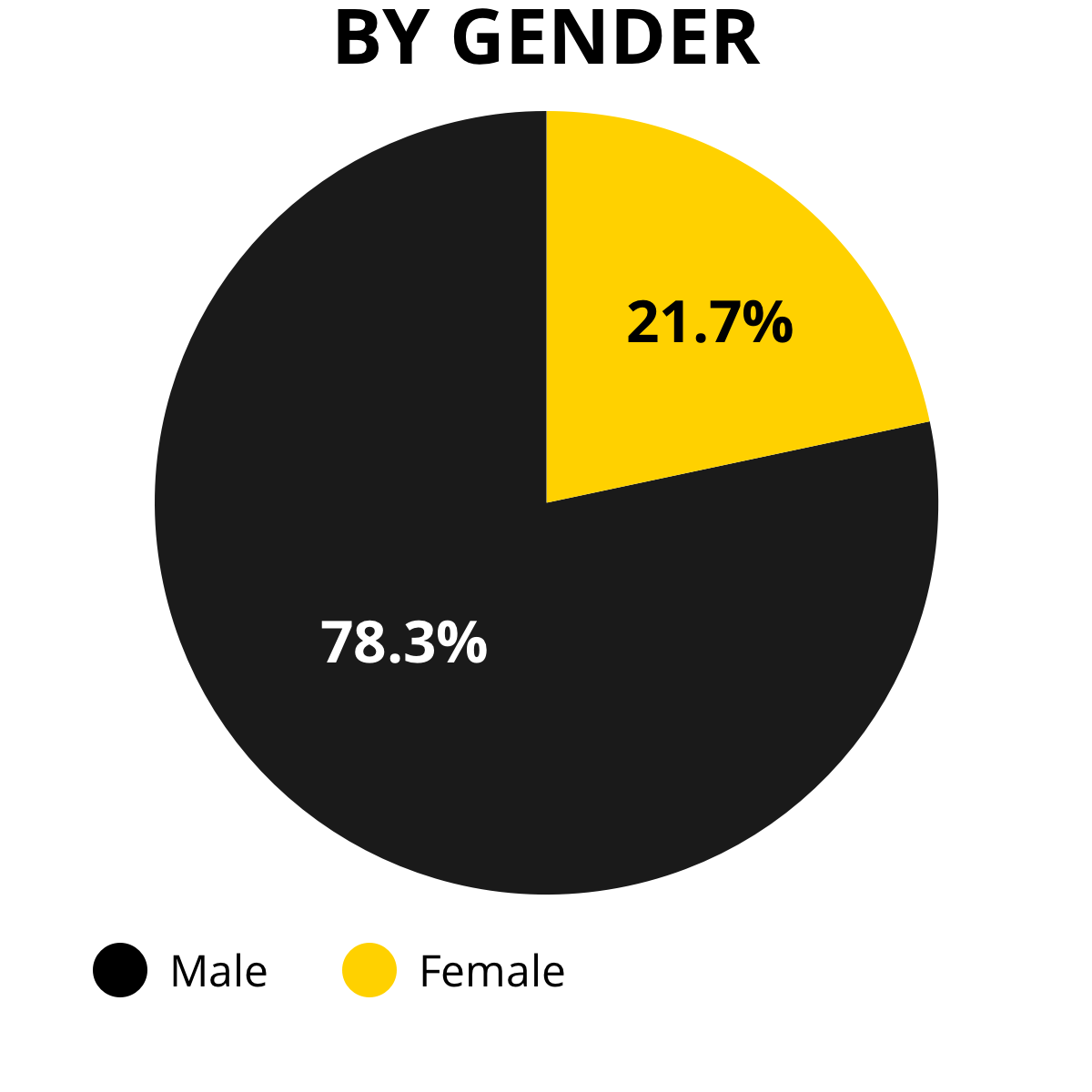

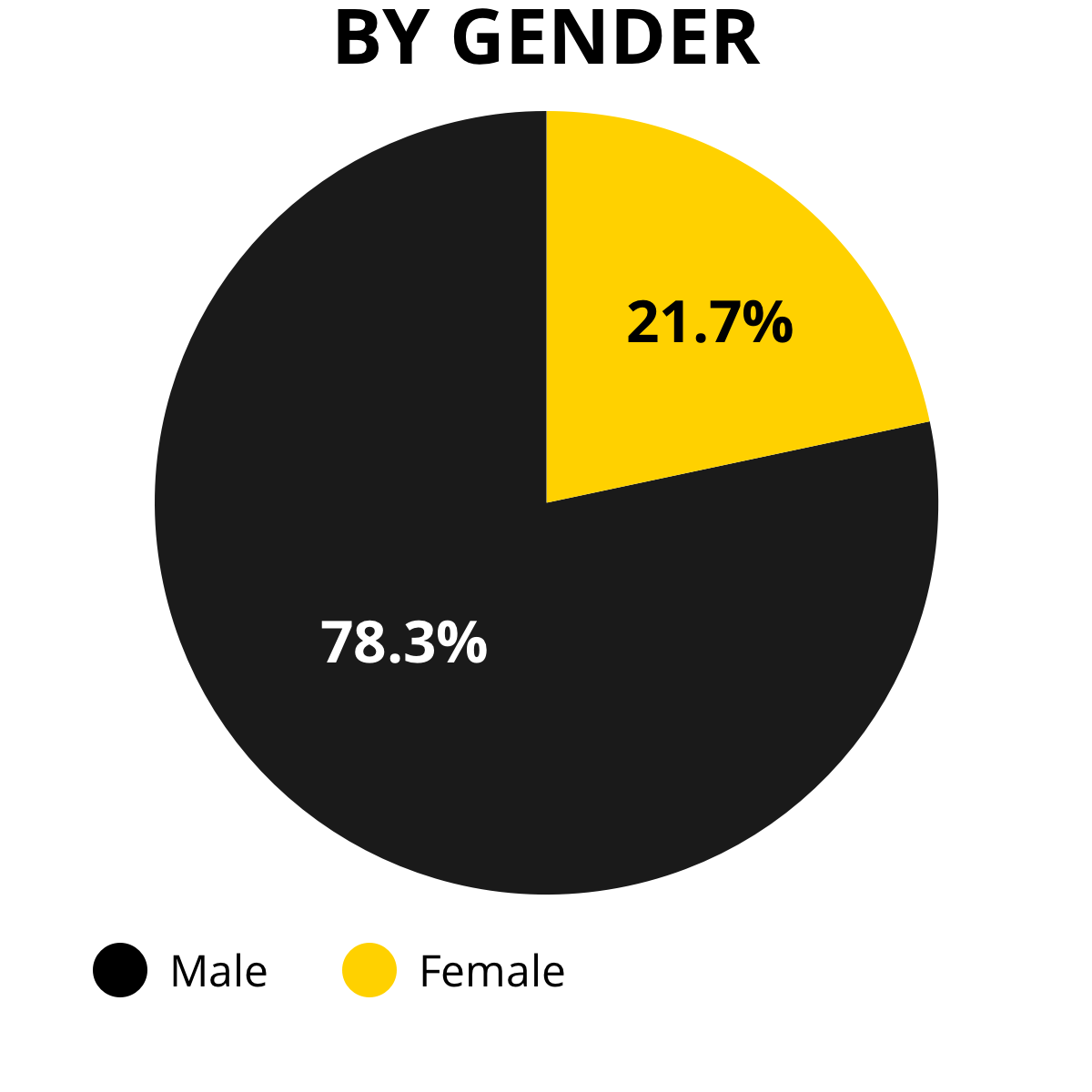

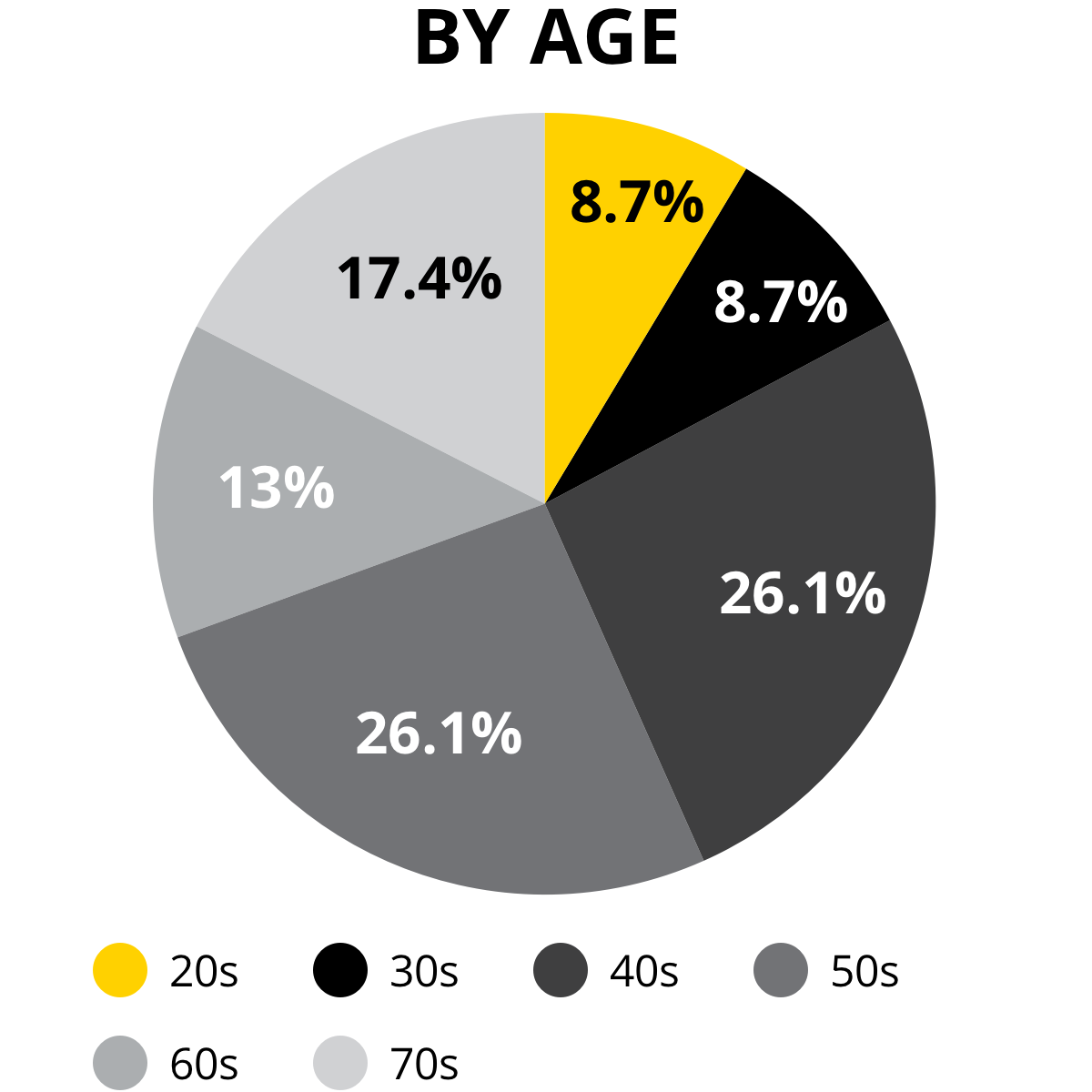

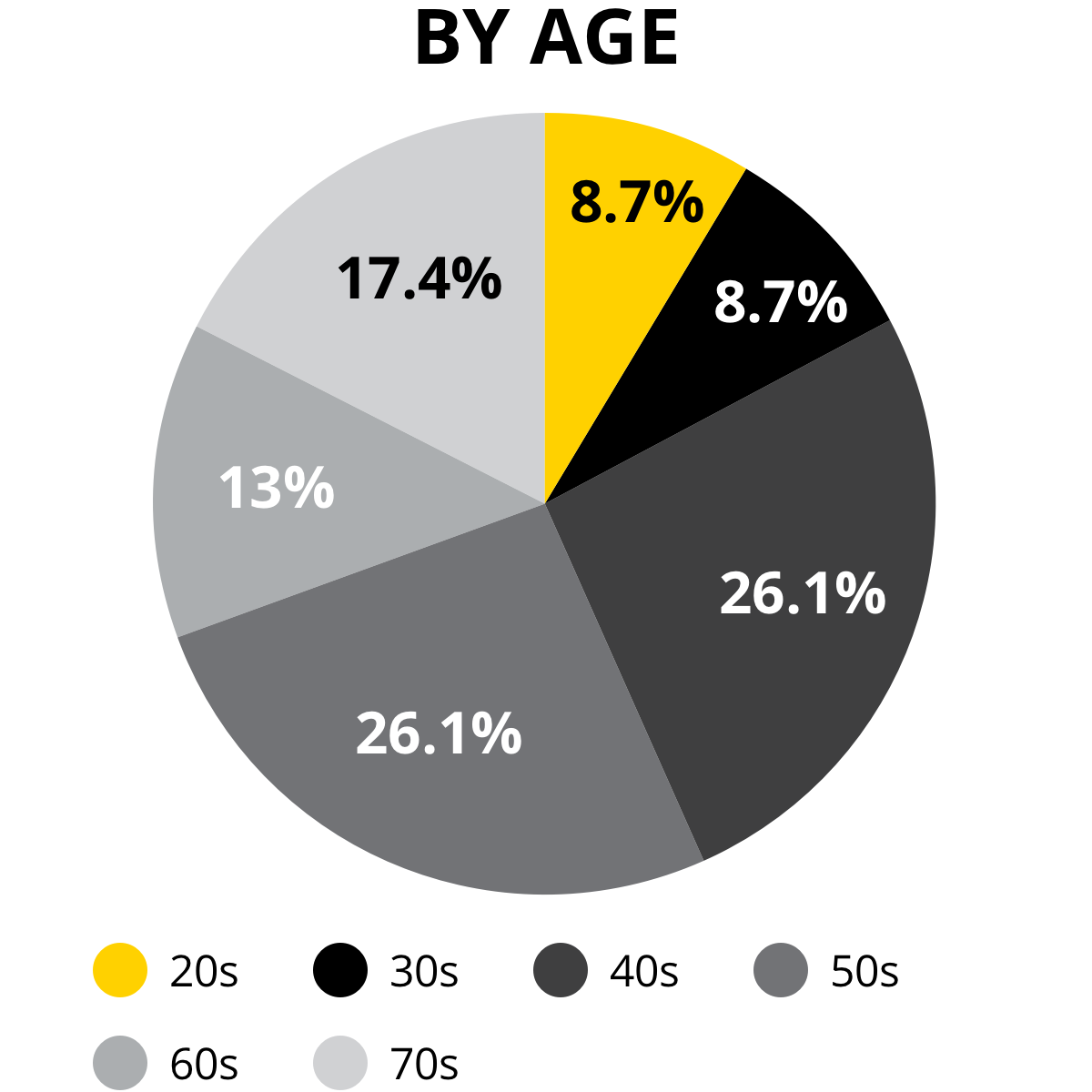

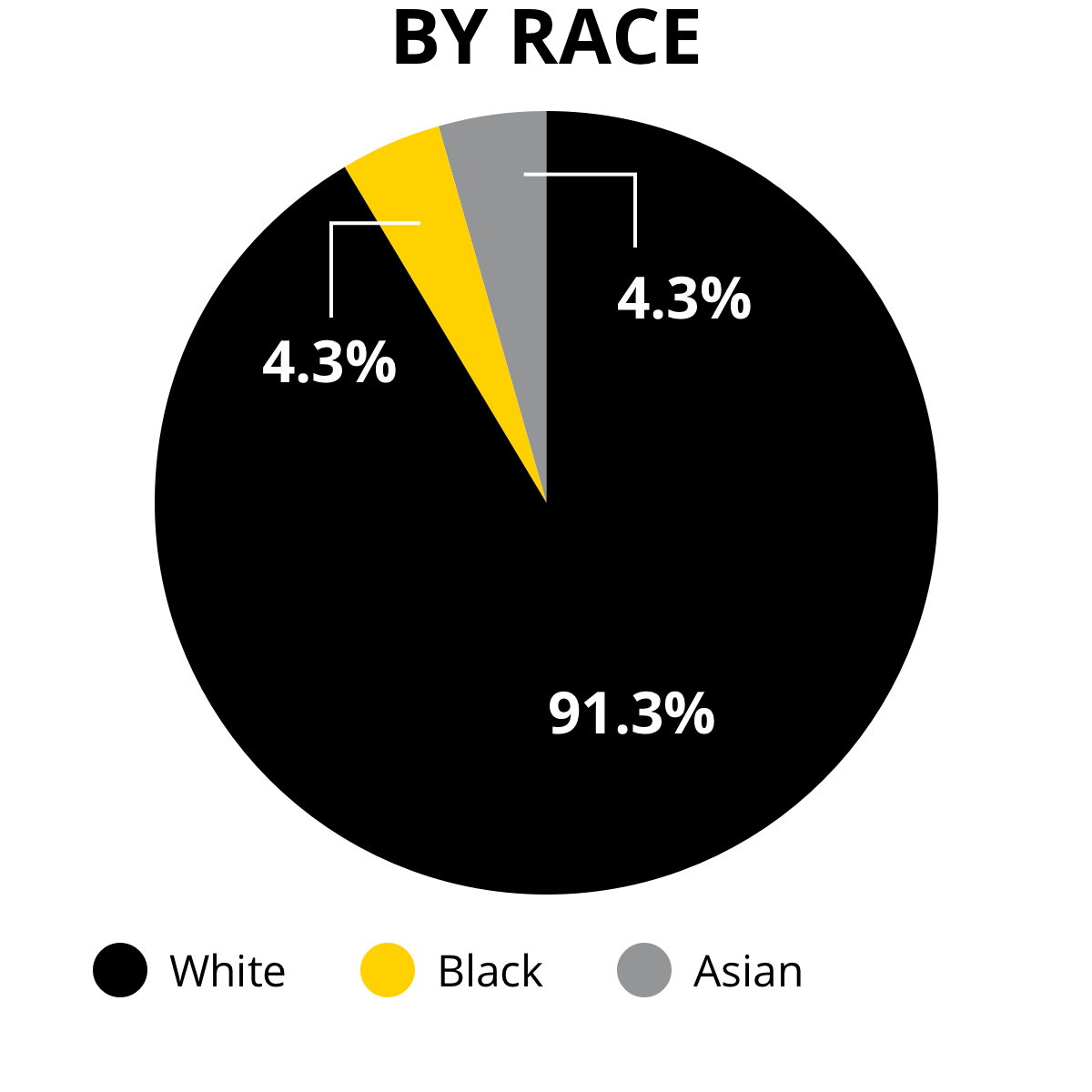

Suicide by fall from height

Cook County, January 2015 through May 2016

SOURCE: Cook County medical examiner’s office. | Frank Main/Sun-Times

Kendra Smith killed herself on May 6.

She was the seventh jumper to die in Cook County in 2016, according to Cook County medical examiner’s records. The others leapt from parking garages, apartment buildings and the Chicago Skyway.

The cause of death each time was recorded as a “fall from height.”

Four hundred and 45 people committed suicide in Cook County in 2015. Just 16 were jumpers.

Most were middle-aged white men. Only a few left any explanation.

One was a 41-year-old man who left notes in his car saying he was crushed by the triple burdens of bankruptcy, divorce and child-support payments. He jumped from the fifth floor of a downtown Chicago parking garage.

Another was a 77-year-old woman who left a note apologizing to her husband for choosing an “immediate cure” to a disease she didn’t name. She leapt from the balcony of her 22nd-floor, Gold Coast apartment.

Most of the jumpers died without a witness. That made Kendra’s suicide even more unusual.

Tim Blankenstein on the roof of his apartment building. He saw a woman jump to her death from the roof of the Luxe building in the background. | James Foster/Sun-Times

Dozens of people saw her final act. Tim Blankenstein went on Twitter afterward: “Sadly, just witnessed someone jump off the roof of a 4 story building in #westloop. Cannot imagine her mental anguish. #shaking.”

I looked up Blankenstein. He lives in a second-floor apartment facing the Luxe.

“She was halfway committed,” Blankenstein said. “She was holding herself up by her arms. I started shaking.

“I took a picture to have evidence that this actually happened. What I felt afterwards was I was just sad, and I felt awful for her, and for that building.”

I understood. I took an iPhone picture, too, of Kendra — a tiny dot — on the ledge.

Blankenstein said he searched online and social media but found nothing about what happened. He didn’t know Kendra’s name or anything about her, “but the image of her will stay with me for a while.”

Emily, a property manager at the building where Blankenstein lives who wanted only her first name published, said she was driving to work when she saw the red fire trucks and an ambulance on Madison Street.

“I thought: ‘It’s a fire alarm. Whatever.’ ”

She parked and walked to an office to make coffee. She reached for a stapler near the window and saw Kendra on the roof.

“I thought: ‘No way I am seeing this.’ It was this eerie feeling. No one was in the office. I got, like, almost ill.”

She noticed the bystanders watching, about a dozen of them on the street.

“One guy was off to the left taking pictures, which I thought was bizarre. Another guy was on his iPhone, taking video.

“What was weird to me was that there did not seem like there was this immense sense of urgency. That’s nothing against the first-responders, but it probably doesn’t faze them as much as it fazes me.”

Emily said she watched for about 10 minutes as Kendra “looked back and forth, contemplating. You could almost see that bargaining or rationalizing or whatever goes through your mind at that moment. I thought, ‘Oh, s---, she’s not coming down safely. Then, she jumped.’

“I remember a girl was in her trench coat, she had her iBuds in, she had a little dress on, clearly walking to work, got stuck in all of this chaos and was talking to someone on the phone. And I remember my eyes meeting hers, and she was just crying.

“I think we, as humans, have a natural curiosity to view these things that are either taboo or something you don’t see a lot, if ever. So I felt the conflict of, ‘I’m curious,’ but I did also feel almost like, ‘It was wrong, it was invasive.’

“That said, she’s choosing to put this display out in front of the public, which almost made me angry. She’s pulling all these people into her karmic web, and it’s kind of like, f--- you, now I have to process all of this s---, too.”

Diana Novak is a former Chicago Sun-Times reporter now covering courts for a website, Law360. She lives in the Luxe building. Her husband was walking their dog at about 7:30 a.m. He saw the woman on the roof but “didn’t think a lot about it because they regularly had workers on the roof,” Novak said.

Novak walked outside to go to work at 8:10 a.m. “There was crime-scene tape to the right of the door. And I saw at least one pink flip-flop laying in the middle of where the tape was.

“It was a nice Friday morning — the first nice Friday morning in a long time,” Novak said.

“Friday should be the day that everything is possible.”

Later, “I saw five ladies with strollers on the exact spot when I came home that night. They were laughing. I don’t know if any of those people knew anything. But I thought: ‘Somebody died there today.’ I was angry.”

She got an email from her building’s management: “I am writing to inform you there was an incident involving our general contractor team this morning. The police are investigating the incident. Please know there are no safety concerns and we will notify you when further information is available.”

There were no later updates, Novak said.

She said someone put a few roses beside the black, wrought-iron fence where Kendra died. “The roses dried up over a few days,” she said.

I knew Dr. Alan Friedman, a Chicago psychologist, from his work evaluating the fitness of police officers and called about what I’d seen.

Friedman said the fact that Kendra was on the roof more than two hours before she jumped suggests she was having a “high degree of ambivalence.”

“Often, a person in this situation has second thoughts,” Friedman said. “Her ego structure said, ‘Don’t do it.’ The longer a person waits — just like in a hostage situation — the bigger chance to negotiate a successful resolution. The fact that she hesitated indicates she was not committed 100 percent to die.”

If negotiators had been able to talk with Kendra, Friedman said they might have been able to suggest things to her about how people would cope with her death better if she died of natural causes — in effect, employing guilt to encourage her not to jump.

He said he understands what people who witnessed Kendra’s death or knew her are going through. In the 1970s, he was a psychology trainee at a hospital in Cincinnati. He and a clinical team evaluated a man for mental illness. The man was released because there weren’t any beds available. His mother was told to keep an eye on him until his follow-up appointment the next morning.

But later that day he jumped off a bridge.

“I felt bad every time I drove under the bypass to get to work,” Friedman said. “We also shared the same birthday. I think of him every single year on my birthday.”

Friedman said a public suicide can create a “ripple effect” among others. The best therapy for someone who witnesses such a death, he said, is to “retell the narrative so you can desensitize yourself and reframe the incident as something that happened to me — not because of me — because a lot of people experience survivor guilt.

“Unconsciously, the guilt that survivors often experience is: ‘I am glad you died, not me.’ ”

I met a lot of Chicago firefighters in New York after 9/11, including Pat Maloney, battalion chief in the Chicago Fire Department’s special operations division. He wasn’t there when Kendra jumped, but he often responds to such calls.

“It’s not just tall buildings where the victims are at,” Maloney said. “You can get jumpers on the expressway, on top of advertisement signs, on bridges, all over the city. I’m not a psychologist, but a lot of times these people are very depressed and are going to jump. But a lot of times, they really don’t want to. They want to see if you can help.”

On June 23, nearly two months after Kendra’s death, Maloney rushed downtown to a Kennedy Expressway overpass where a man who’d slashed his hands and neck with a box-cutter was sitting on a ledge.

The Illinois State Police stopped traffic on the expressway below, and firefighters set up an airbag — one of three kept at firehouses citywide. A firefighter cut out a section of fence surrounding the overpass to provide access to the man.

“The guy was saying his family didn’t want him any more,” Maloney said. “When he put his knife down on the ledge, a fireman kept him busy, talking to him. I knocked off the knife with a pole to eliminate that threat. Then, we made the decision to lower the Special Ops firefighter. He got to him and held on to him, pretty much bear-hugged him. Tower 10 raised their basket to us, and we were able to bring him down.

“That was a good day.”

The day that Kendra jumped, Maloney spoke with some of the firefighters who’d been there. “I told the guys, ‘You did nothing wrong. If someone wants to jump, they’re gonna jump.’ ”

Maloney introduced me to Battalion Chief Thomas Arnswald, who, during his 36-year career, has answered about 10 calls involving jumpers. Most were dead by the time he got to the scene or rescued by firefighters or police. Kendra was the only person he saw jump to her death.

“This one was tough,” said Arnswald, who supervised the rescue attempt. “We did everything we could do. She just made up her mind she was going to jump.”

About 25 firefighters and paramedics were on the scene. Arnswald said he took the stairs to the roof with a paramedic and two firefighters. A rectangular, concrete partition on the roof blocked their view of Kendra except for her dangling legs.

Arnswald’s plan was that a firefighter with ropes and a harness would hide behind the partition with a second firefighter without a harness, and he was going to have the female paramedic approach Kendra, thinking she might relate better to a woman.

While Kendra’s attention was occupied by the paramedic, the firefighter with the harness would grab her, with the second firefighter ready to help.

But Kendra jumped before they could get to her.

Arnswald spoke afterward with the firefighters on the ground. Some of the older firefighters had watched her land, the chief said, while the younger ones turned away.

Arnswald said he walked down the sidewalk on Madison Street and was surprised to see people in the ground-floor exercise studio at the Luxe building working out on treadmills and stationary bikes.

“I don’t know if they knew what just happened or not, but it was like ‘life goes on.’ That’s the image I can’t forget.”

He, too, scoured the Internet for information about Kendra but didn’t find much and gave up.

In recent years, the Chicago Fire Department has made treatment for post-traumatic stress a priority. After Kendra’s suicide, the firefighters and paramedics who’d been there reconvened at a nearby firehouse at 324 S. Desplaines St. A fire department counselor talked with them for about 40 minutes.

“She did most of the talking,” Arnswald said. “These are firefighters. They didn’t have a lot to say.”

Dan DeGryse, another battalion chief, said he worries about the stress that firefighters experience. Over the past 25 years, an average of two Chicago firefighters a year have committed suicide. Their average age: 54.

DeGryse is one of the founders of the Rosecrance Florian Program, which helps firefighters deal with psychological trauma. He speaks around the country about the need for first-responders to talk about the things they see on the job.

“We might save 1,000 lives a year, from fire victims to car crashes to potential jumpers, but the ones we lose are the ones that trouble us,” DeGryse said. “Many of us are Type A personalities — athletes. And when we are not successful, that tears us up.”

I had put off calling Kendra’s mother, Shirley Ann Williams, but, through friends of Kendra I’d spoken with, she passed along word she wanted to talk.

“Some days. I can’t get out of bed,” said the 71-year-old Williams, who lives alone in a Cincinnati suburb and described herself as “beyond broken” by her daughter’s suicide.

She described Kendra’s upbringing as alternately idyllic and troubled.

When Kendra was young, Williams and her husband were AT&T executives. The family lived on a rambling, 45-acre farm outside Nashville, Tenn., where Kendra helped with the pigs and cows and worked on cars with her dad.

“She was her dad’s girl,” Williams said.

She said her daughter excelled in her classes, was a cheerleader at White House Middle School and was passionate about helping the disadvantaged, even giving them some of her things.

“She would pick out expensive clothes. If I went to a band concert, I might see that sweater on a girl sitting up in the stands. Kendra had a heart.”

When AT&T transferred Williams and her husband to Atlanta, Kendra was unhappy to be uprooted from her friends, according to her mother. Then, her father was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. In her teens, Kendra slid into cocaine and alcohol abuse while her father struggled with cancer. She was diagnosed as suffering from bipolar disorder and admitted to a psychiatric hospital, her mother said.

“She was very angry,” Shirley Ann Williams said. “She hated me. And she held that against me for the rest of her life.”

I wanted to know more. And Kendra’s mother needed to talk.

She told how Kendra’s father died two years after his cancer diagnosis. That crushed her, according to the mother, who said she struggled in high school and was going to quit her senior year until she begged her not to.

She graduated but didn’t go on to college. She married someone from a wealthy family, her mother said, but the marriage soon ended in divorce. Then, she married an older man in Florida her mother said was an alcoholic and abusive. That, too, ended in divorce.

Kendra landed a job with a real-estate company, traveling the country marketing distressed properties, her mother said.

That’s how she met her future husband, a suburban Chicago businessman. They got married in 1998. They had two children and lived in a big house in the northwest suburbs. It was the start of one of the best periods of her life, according to her mother.

She said Kendra was working for her husband’s company, making more than $75,000 a year.

“Her children went to private schools,” she said. “She did charity. She was the chairman of everything. She did things for the school. She was just perfect.”

Eight years into the marriage, though, Kendra again was abusing cocaine and alcohol and, in 2006, twice threatened suicide, her mother said — once putting a gun to her head and the other time overdosing on Xanax.

She said it was too much for the husband, and they divorced in 2006.

He declined interview requests.

Court records show Kendra was awarded $500,000 in the divorce, plus $2,000 a month in child support. At first, she shared custody of their children — a boy and a girl. But that ended in 2009, after she was arrested for a break-in, and he won a court order barring her from seeing her kids again.

The break-in involved a man Kendra was dating, John Bradley Crenshaw, court records show. They went to a block party in the northwest suburbs, where she was living. She and Crenshaw left the party and broke a neighbor’s window with a baseball bat to steal jewelry, a coin collection and a credit card.

Days after the break-in, her babysitter called Kendra’s ex-husband in tears, saying she’d gotten a text from her saying she and Crenshaw “did some bad things,” and she didn’t want the kids to see her arrested. She’d also left notes saying goodbye to her young son and daughter.

The babysitter rushed the kids to the ex-husband’s home. He got a court order of protection against Kendra to keep her away from the children, who he said were “confused and shocked. They fear and worry over their mother’s well-being. I do not want my children traumatized by seeing their mother arrested, overdosing or committing suicide.

“I do not know what she is capable of at this point,” her ex-husband wrote.

Kendra and her boyfriend were arrested and charged with burglary. She begged a judge to let her speak on the phone with her kids and write them letters.

“Once I get out I am willing to do anything it takes to work towards having my children back,” she wrote.

The judge denied her request.

Crenshaw ended up going to prison. Kendra escaped a prison sentence, getting probation, but she couldn’t escape her problems.

“I don’t blame Kendra for it. She had a disease.”

— Shirley Ann Williams, Kendra’s mother

Those centered on drugs, according to her mother and court records.

To pay for them, she stole tens of thousands of dollars from her mother’s bank account and looted her home, Shirley Ann Williams said, even taking her wedding rings.

“She would come down on the Megabus and take everything,” her mother said. “Hundreds of thousands of dollars of jewelry. I have nothing now.”

But she didn’t have her arrested.

“I don’t blame Kendra for it,” she said. “She had a disease.”

In 2012, Kendra was arrested on a felony drug charge in Cook County. She was sentenced to “intensive drug probation” involving treatment.

The following year, she was busted for defrauding a property-management company where she was working and also for stealing computer equipment, records show.

Held at the Cook County Jail while awaiting trial on felony theft charges, she worked as a tutor in a high school diploma equivalency program and was an “assistant motivator.” She told her counselors “her goal is sobriety,” court records show.

She was convicted of the theft charges in 2014 and sent to prison that April. She spent six months behind bars.

“Other women did unspeakable things to her in there,” her mother said.

When she was freed in September 2014, Kendra made a commitment to herself: This time, finally, she’d find a way to climb out of the dark hole that had become her life.

She got involved with a group called Back on My Feet. It’s a national not-for-profit organization that offers support in finding housing and jobs to combat homelessness and uses long-distance running as a way to help rebuild lives.

Kendra joined Back on My Feet after getting out of jail. She was staying at Grace House, a halfway house in the West Loop.

“When she started out, she could barely run a couple of blocks,” said Kathy Higa, a Back on My Feet volunteer. “But when she put her mind to something, she could accomplish it. She was our bright shining star.”

Kendra ran at the crack of dawn on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays with the running group.

“Kendra was, like, the fun one, the loud one,” Higa said. “She would liven up every run, get people in good spirits.”

Shayna Sims, another Back on My Feet volunteer, said she and Kendra trained to do a half-marathon together.

“I asked, ‘Who are you looking forward to talking to at the end of the race?’ ” Sims said. “She told me it was her mom. We got to the finish line, and everybody was crying. She called her mom up on the phone. She’s crying. We’re all crying.

“She said, ‘Mom, I did it.’ From then on, she encouraged so many people. She was like a cheerleader.”

Kendra got a job at a Dunkin’ Donuts on the Near West Side and enrolled at Kennedy-King College to get an associate’s degree in addiction studies — which she had nearly completed at the time of her death.

She moved out of Grace House and got an apartment with roommates in West Rogers Park.

Through Dalmanic Simmons, another ex-offender she became friends with through Back on My Feet, she landed a job renovating a mansion in Hyde Park.

“Kendra walked in and started busting her ass,” said Francisco Vargas, who met her through Back on My Feet, worked on that job and became her boyfriend. “She used to pick up a 4-foot-by-8 piece of dry wall and walk it up to the third floor. A lot of men fell in love with her.”

In October 2015, Kendra ran the Chicago Marathon — becoming one of the first members of Back on My Feet to accomplish that.

“I forgot what mile it was, she was swelling in places and stopped at a medical tent,” Sims said. “She decided to get up and finish it. She pushed through it.”

At Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, Kendra would tell her comeback story. People would beg her to be their AA sponsor.

Kendra Smith from Jan. 13, 2015, appearance on ABC7’s “Windy City Live.” WATCH NOW

On Jan. 13, 2015, she went on ABC7’s “Windy City Live” and talked about her experience with Back on My Feet.

“I’m a convicted felon,” she said in the TV appearance. “And with my transition from prison to having to reenter into society, there aren’t really a lot of options.

“People want to point the finger. And, you know what, we might have made a mistake. But we’re not a mistake. They treat us with the respect we deserve and the dignity, and you walk away with hope and with faith that we can do it. And it is a family.”

But she still ached to see her kids.

“Going back to school was for the purpose of trying to prove that she had changed so she could get custody of her children again,” Simmons said. “That was her No. 1 goal.”

Vargas is 35, about nine years younger than Kendra. He describes himself as “kind of antisocial.” When he met Kendra, “I was, like, ‘When is she going to shut up?’

“She was very intelligent, and she would correct me. I was, like, ‘Oh, God, I work in construction, not in an office in the Water Tower.’”

Still, they became inseparable, getting an apartment together on the Northwest Side.

She landed a job at WeWork, an office-sharing company on the Near West Side. She managed the janitorial work there, hiring friends from Back on My Feet.

“She was always helping people,” Vargas said.

Last November, Kendra started working for Summit Design & Build, supervising the rooftop project at 1222 W. Madison. She was proud to have gotten the job but worried she might lose it after doctors found a problem with one of her kidneys, according to Vargas.

“She couldn’t eat at all,” he said. “She would eat something and throw it up. She was only taking in Pedialyte. They told her she could live with one of her kidneys.

“It was bad. I kind of took care of her at night. She couldn’t sleep.”

On May 4, she told Vargas and a roommate who lived with them a doctor had said she might have cancer. Vargas said she told them, “I don’t have long to live.”

“She was mad. She was angry. She said, ‘I went through all of this, and now they’re saying it might be cancer?’”

On May 5, late in the day, Kendra told Vargas she needed to go to work for an emergency, which he said wasn’t unusual. He noticed something that was, though, in a closet: her work boots, the size 6, steel-toed Timberlands he’d given her as a Christmas present, which she always wore to the job.

“I thought that was kind of weird,” he said.

On May 6 — the morning of her death — at 4:39 a.m., Vargas got the text message from Kendra, saying, “I love you.”

He tried to call and, worried he couldn’t reach her, texted “Are you OK?” at 1:28 p.m.

At 1:29 p.m., he got a text: “Call Detective Turner.”

Vargas met with Detective Glenn Turner at the police station at 51st and Wentworth.

“They told me she jumped off the building. ‘Not Kendra,’ I said. ‘She would never do nothing like that.’”

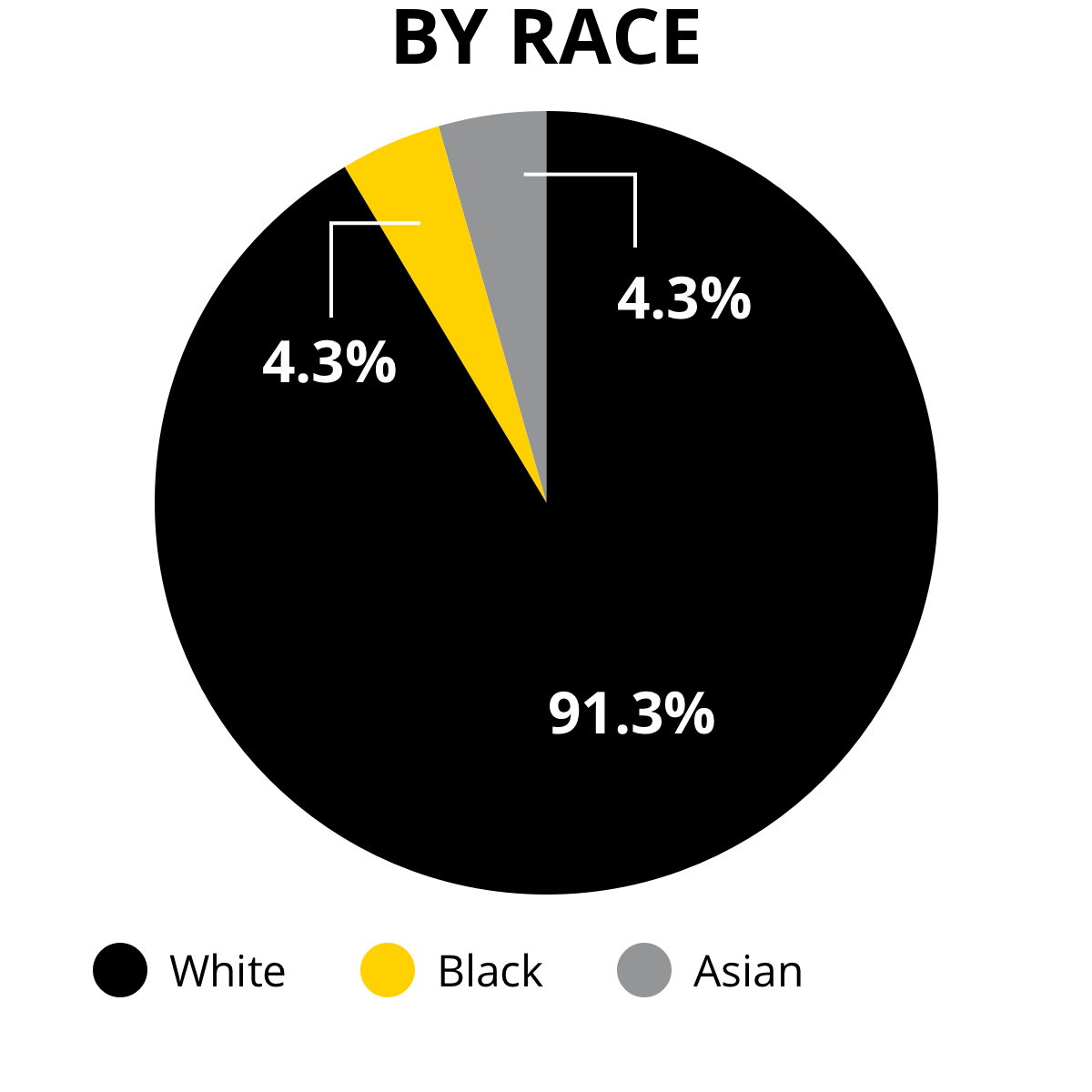

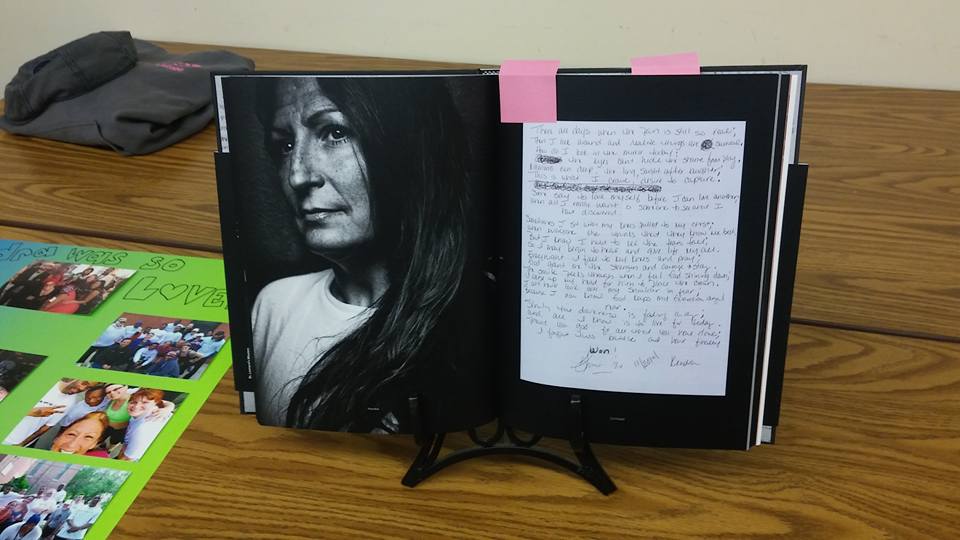

At Kendra Smith’s memorial. | Provided photo

Vargas arranged the memorial service. There was an open casket. Kendra was dressed in her Chicago Marathon jacket, with her marathon participation medal around her neck.

Her teenage son and daughter came with Kendra’s former husband. Vargas gave the children their mother’s Chicago Marathon bib, No. 46330. It was a complete surprise.

“They didn’t know she ran it,” Vargas said.

He keeps some of Kendra’s ashes in a vial on a necklace. He doesn’t wear it. “I keep her in the bedroom,” he said, the same room where her Timberland shoes are still in the closet where she left them.

Since Kendra left no explanation of why she killed herself, Vargas, her mother, her friends and others touched by her life and her death are left ultimately with no certain answers. They can’t even find out whether she did, in fact, have cancer. Her mother and Vargas asked but said Kendra’s doctor would not confirm that for either of them.

Her friend Dalmanic Simmons thinks she must have and that she committed suicide “so we wouldn’t suffer.

“She was that kind of person,” Simmons said.

Her mother tries to focus on the positives in her daughter’s life.

“It’s kind of a riches-to-rags-to-riches-to-rags story,” she said. “She gave so much of herself to needy people. But she couldn’t do it for her family for some reason.”

There are no neat endings here. Kendra hurt a lot of people. She inspired a lot of people, too.

I’m not really sure what I was looking for.

But now, at least, I know who the woman was on the ledge.

WHERE TO TURN FOR HELP

National Suicide Prevention Hotline, operates 24 hours a day:

1 (800) 273-TALK (8255)

Surgeon General's suicide-prevention website:

www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/national-strategy-suicide-prevention/

For those who've lost someone to suicide:

http://www.catholiccharities.net/GetHelp/OurServices/Counseling/Loss.aspx

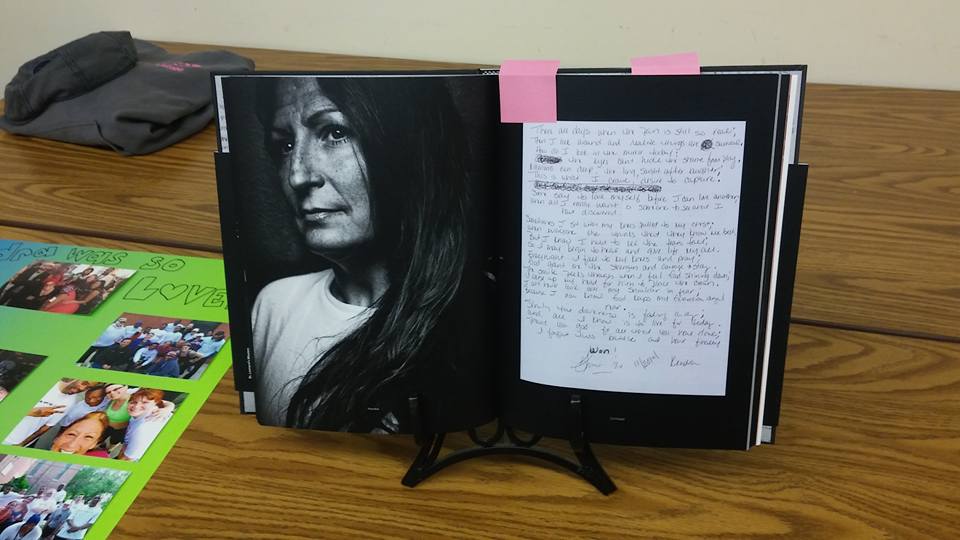

Francisco Vargas holds a necklace containing ashes of his late girlfriend Kendra Smith. | Max Herman/Sun-Times

Support our journalism

Become a Chicago Sun-Times subscriber today to support stories like this one.